Design and support of a flexibility-centric energy and cross-sector value chain

Article by José Villar, Luís Rodrigues, Ricardo Bessa, Fabio Coelho e João Mello, from INESC TEC.

As the decarbonization of the power system progresses, the penetration of renewable energy sources (RES) increases and conventional fossil-fuelled power plants, which are easily dispatchable and traditionally the main providers of system flexibility, are also being decommissioned. Flexibility is usually defined as the ability to adjust generation or consumption patterns in response to external signals [1].

With the increase of RES with high variability and low or no dispatchability, balancing production and consumption is becoming increasingly challenging [2], which largely explains the need for new sources of flexibility [3]. At the same time, the increment of distributed energy resources (DERs) increases the complexity of distribution grids operation and the needs of additional flexibility to help dealing with grid constraints [3], such as voltages out of their nominal ranges or lines overloaded, where these can be resolved with cost-effective activation of flexibility rather than network reinforcement.

The European Union (EU) is urging its member states to formulate regulatory frameworks that allow and incentivize distribution system operators (DSOs) to procure flexibility to operate and develop their grids. In addition, whenever possible, flexibility shall be procured through a transparent, non-discriminatory, and market-based procedure [1].

The deployment of flexibility, particularly demand-side flexibility, requires digital infrastructures capable of ensuring a secure and reliable data access and exchange between parties [5]. Thus, over the last few years, multiple flexibility market platforms have been conceptualized and deployed to support DSOs in procuring and leveraging flexibility [6], [7], most of emerging in pilots or regulatory sandboxes.

More recently, in 2023, the EU DSO Entity and ENTSO-E set out a proposal for a Network Code on Demand Response which compels member states to require system operators (SOs) to publish information related to flexibility procurement on a single platform at national level [8].

However, the involvement of end consumers in the provision of flexibility is an important challenge that requires new strategies to simplify processes and increase the value of providing flexibility.

Flexibility-centric energy and cross sector value chain

The characterization of the flexibility-centric energy and cross-sector value chain (FCVC) was one of the tasks of the BeFlexible project to identify the main stages and business needed to engage end consumers in the flexibility provision activity, identify new business models (BMs) that could add value to their participation in flexibility provision, and the interactions among all actors involved in the business models. The potential BMs are described in [9] and their identification was a preliminary step to build the FCVC.

The core value of the FCVC is in its ability to pair stakeholders and link them with profitable BMs. This can be supported by digital tools and platforms, such as the Grid Data and Business Network (GDBN) and the services it provides, to coordinate and exchange data between flexible assets, flexibility service providers (FSPs) and SOs who join the FCVC. Ultimately, the FCVC supported by the GDBN will facilitate the participation of end consumers in flexibility markets, while ensuring that DERs are easily accessible to all parties, unlocking the potential flexibility of consumer-side assets.

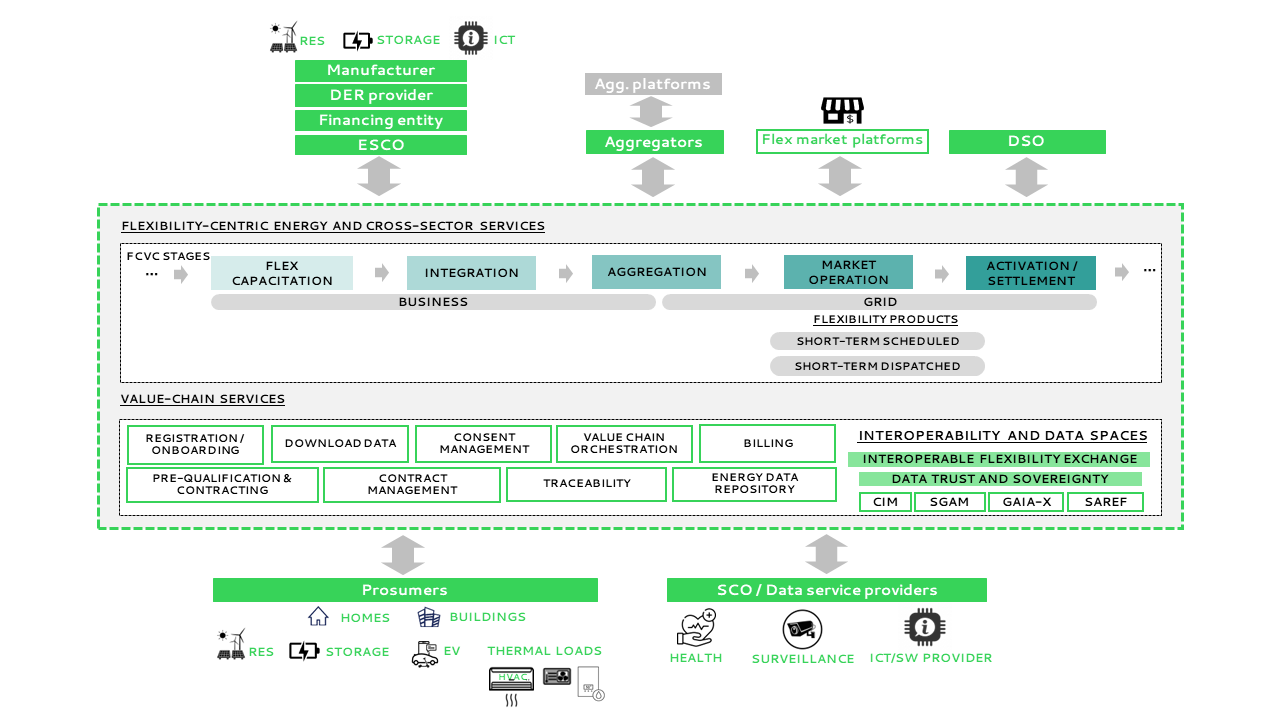

The FCVC includes 6 primary stages: flexibility capacitation, integration/enablement, aggregation, negotiation preparation, market operation, and activation & settlement, as depicted in Figure 1. For each stage, the primary and secondary activities and the main roles involved are identified. While the first two activities of the FCVC (acquiring new or retrofitting existing assets and enabling them to provide flexibility) are occasional activities, the remainder ones execute periodically, as depicted in Figure 1. Nonetheless, specific activities of the periodic stages may also run occasionally.

Click the icon beside each step to view more information:

Figure 1 – Structure of the flexibility-centric energy and cross-sector value chain.

The Grid Data and Business Network to support the FCVC

The GDBN is a digital platform to support the main stages of the FCVC and to enable secondary activities for the FCVC stakeholders, facilitating the different processes and contractual agreements involved, as an engagement driver to unlock flexibility provision. The GDBN can integrate third parties’ services and digital platforms, such as commercial LFM platforms already available, and provide services such as the flexibility activation, often not part of LFM platforms.

Moreover, the interoperability enablers in the GDBN link each FCVC stage, supporting the interoperable data exchange requirements and future proofing the concept. Finally, the FCVC presents a framework for all flexibility stakeholders to acquire flexible assets, find attractive BMs, and handle asset control and mobilisation. For consumers it provides a low-cost and simple solution. For businesses, it helps to find and match clients and partners, and to explore the intrinsic value of flexibility data within them, while promoting sustainable BMs to reduce shortage of flexibility in the power system due to unattractive value propositions. This FCVC is a result of the BMs and role model identified and described in [9], departing from [7] and [8].

Figure 2 – The structure of the Grid Data and Business Network.

The GDBN architecture is built from a series of modules that ensure the operation of the FCVC:

- The flexibility-centric services module sets the service for the core stages of the value-chain to capacitate consumers to leverage their flexibility potential, to integrate, aggregate and take the flexibility offers to market and afterwards receive activation requests from DSO.

- The flexibility products module if for installing a tiered service proposal for adopters of the GDBN solution, including the short-term scheduled and the short-term dispatched.

- The value-chain services module includes basic services such as user accounting for all stakeholders, but also consent management over all flexibility related data exchanges, and most importantly, the repositories of flexibility bids, activations, and the assets available in the flexibility zones where the GDBN actively provides services.

- The interoperability and data spaces module accounts for the interoperable and standard data interfaces available for the inclusion of stakeholders’ digital platforms and external market platforms considered in each stage.

The proper identification and design of the FCVC is an essential step in the development of new digital platforms, such as the GDBN, to engage end customers in flexibility provision, facilitating the development of the FCVC stages for all involved actors, matching consumers and services providers and fostering new cross-sector business models that add value to the flexibility provision.

The GDBN aligns with European regulations which guide SOs to publish flexibility procurement information on a common platform at national level, a key factor given the increasing number of emerging flexibility market platforms. A successful implementation of the GDBN platform will represent a significant advancement in the digitalization of energy systems focusing on flexibility provision.

This article summarizes key takeaways from Deliverable 1.2, titled “Framework for a flexibility-centric energy and cross-sector value chain, business use cases and KPI definition” developed within the framework of the BeFlexible project. To access the complete document, please click here.

Stay tuned with BeFlexible by following us on LinkedIn and X!